Galleries and institutions across the city are highlighting historic and contemporary Indian artists, including modernist Nasreen Mohamedi, painter Atul Dodiya, and photographer Soumya Sankar Bose

Globally known as the financial capital of India, Mumbai places equal emphasis on the preservation of the country’s rich art history without losing sight of the contemporary. Throughout history, and up until today, the city’s flourishing creative scene has fostered a culture of diversity and belonging: Mumbai was once home to the pioneering Progressive Art Collective, whose legacy continues to be seen in the recognition of art as a form of dissent and change in an age afflicted with myopia, while events like the Kala Ghoda Festival and Mumbai Urban Art Festival act as symbols of the city’s interconnectedness.

This season, galleries and institutions in Mumbai are reflecting such ethos, presenting works by a spectrum of established and emerging Indian artists who, through their experimentations in genre, format, and form, illustrate various facets of their country’s history. These five exhibitions in particular are worth noting.

Simryn Gill and Anwar Jalal Shemza, ‘Contact’

Jhaveri Contemporary

Through February 25, 2023

Featuring photograms by Anwar Jalal Shemza and Simryn Gill, this exhibition highlights the contrast between the organic and inorganic. Shemza’s untitled photograms from the 1970s depict scissors, hands, and clippings of flowers, plants, and shrubs from his own garden, while Gill’s series, ‘Clearing’ (2022), features the leaves and stems of a century-old Canary Island date palm.

Beyond their natural subject matters, the process of producing photograms adds an additional layer of context. Photograms are created by placing objects directly on the surface of a light-sensitive material, such as photographic paper, and shining light onto it. As the object and paper are exposed to the light, the object’s shadow appears as the image. With transparent or semi-transparent objects, like leaves, the resulting visual takes on a ghostly aura, inhabiting the liminal space between reality and fiction.

Here, the artists’ works reveal geological features, venation, fossils, and vascular systems; but the subtle gesture of making contact with the images’ subjects – another inherent part of the photogram process – also serves as a foil to the distance that is often maintained when producing the digital images that occupy our contemporary lives.

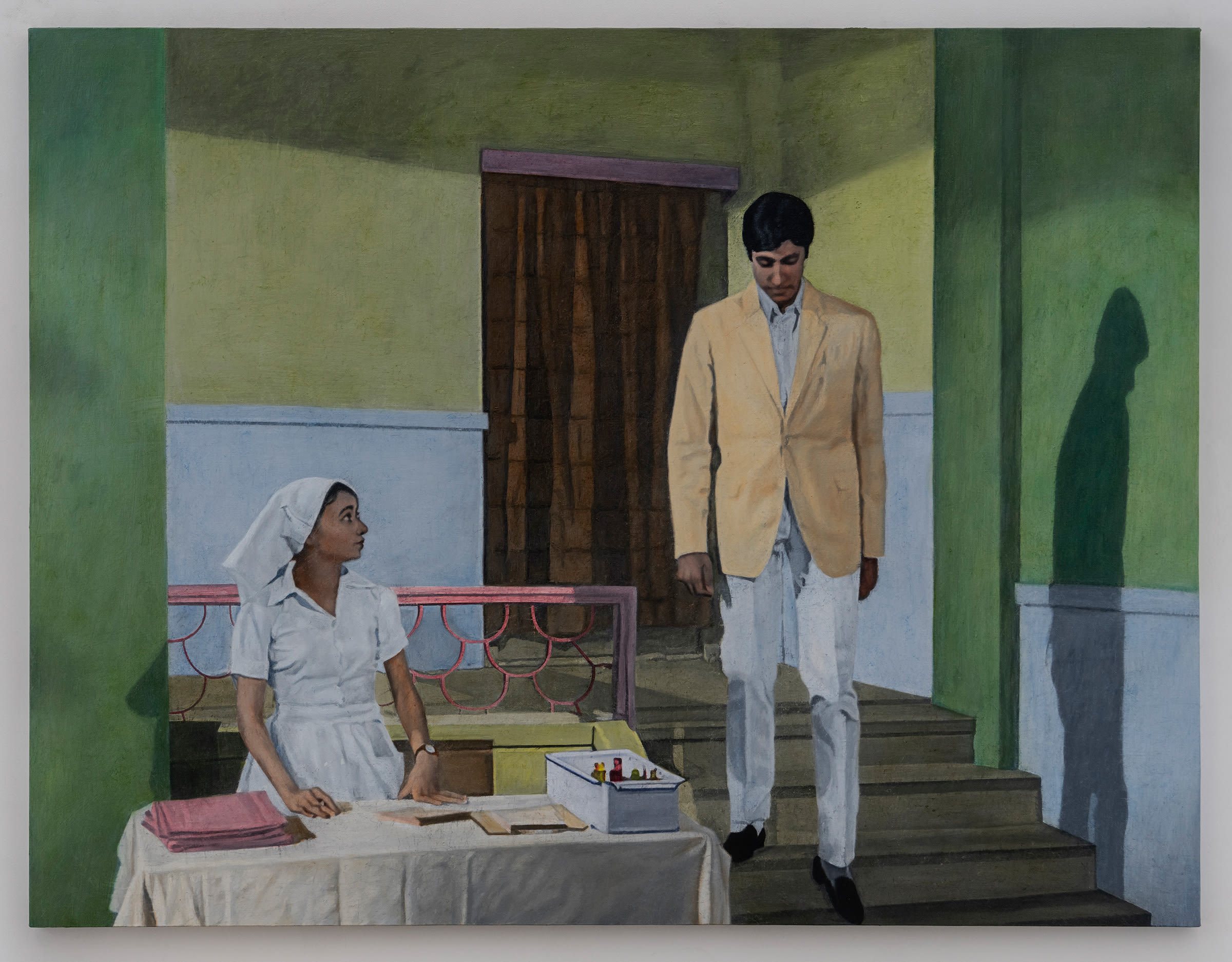

Atul Dodiya, ‘“Dr. Banerjee in Dr. Kulkarni’s Nursing Home” and Other Paintings 2020-2022’

Chemould Prescott Road

Through February 25, 2023

During the pandemic, Mumbai-based painter Atul Dodiya took to rewatching some of his favorite movies, such as Anand (1971), Anuradha (1960), Barsat (2005), Kapurush (1965), and Padosan (1968); while watching, he used his iPhone to photograph scenes when the actors’ backs were turned to the camera. These frozen moments then became sites to explore the mystery shrouding the subjects by way of larger-than-life paintings – now on view at Chemould Prescott Road. In Karuna (2022), for example, the protagonist from Kapurush rummages through the drawer of a dresser. In Anand with his book of poems (2022), the titular character from the movie walks away from the viewer holding a book in his left hand. Seen as a whole, the suite of 24 paintings (the number of works itself a nod to the 24 frames per second at which traditional cinema is shot) combine existing references to create a new fictional world.

Nasreen Mohamedi, ‘The Vastness, Again & Again’

Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation

Through April 30, 2023

Throughout her artistic practice, Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–1990) used lines as a metaphor for the boundaries between the personal and public lives of people, especially women, in newly independent India. Specifically, she layered and bent lines in minimal and monochromatic works to counter the absolutism of straight cartographic borders and stark religious binaries that resulted from the Partition of India in 1947.

This exhibition features a selection of the artist’s drawings, paintings, prints, etchings, and lithographs, as well as archival photographs, sketches, and studio notes, alongside works by a few of her contemporaries, like VS Gaitonde, Pilloo Pochkhanawala, Jeram Patel, and Nalini Malani. As such, the exhibition not only sheds light on Mohamedi’s singular practice but also conveys her lasting legacy and the broader significance of Modernism in India.

Apnavi Makanji, ‘PSYCHOPOMP’

Tarq

Through March 1, 2023

Mumbai-born, Geneva-based artist Apnavi Makanji’s practice is rooted in the themes of post-colonialism, extractivist histories, and queerness – all of which are explored in ‘PSYCHOPOMP’, their second solo show Tarq.

The exhibited drawings, collages, sculptures, and videos use elements of botany, ecology, and memory to represent popular yet flawed understandings of our ecosystem. The installation Styx (2020), for example, juxtaposes found objects, such as cast dental plaster, soil, and bones, with blueprints of crude oil extraction sites in West Africa owned by the French petroleum company Elf. In this pairing, Makanji underscores the intertwined legacies of slave labor and corporate extractivism, which today perpetuate neo-colonialism. Simultaneously, collages like Hathor (2022), P.H.A.N.S.T.R.O.M.A.K. (2022), and APIS (2022) invite viewers to see the world through a prism of queerness, encouraging a move away from the anthropocentric perspective.

Seen together, the works in ‘PSYCHOPOMP’ combine to propose what Makanji deems a ‘queertopian world’ – one that is built on the collective and intersectional awareness; that is inclusive of not only the human species but also the botanical and mineral abundance of nature.

Soumya Sankar Bose, ‘A Discreet Exit through Darkness’

Experimenter, Colaba

Through March 5, 2023

Known for his documentary photography, Soumya Sankar Bose ventured into a new format for his debut solo exhibition in Mumbai: virtual reality. The show is centered around the titular 360-degree VR film, A Discreet Exit Through Darkness (2022), which sifts through an unsettling mystery in his family’s history: When his mother was nine years old, she was sent to run an errand – specifically, to purchase sweetmeat for the family shrine – but she disappeared. When she suddenly returned over three years later, she had no recollection of what had happened as a result of prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize faces. In the film and an accompanying series of photographs, Bose attempts to fill this void by re-imagining situations based on his excavations of the family’s visual archives and his conversations with relatives. Here, the format of VR itself – which does not allow viewers to see the entire visual at once – plays an important role, as it mimics the gap in his mother’s memory; the viewer, like Bose’s own process of discovery, must piece together different perspectives and connect missing links.

Dilpreet Bhullar is a writer and researcher based in New Delhi and Mumbai, India. She is currently the editorial manager of TAKE on Art, a magazine dedicated to South Asian contemporary arts.

Source : Art Basel