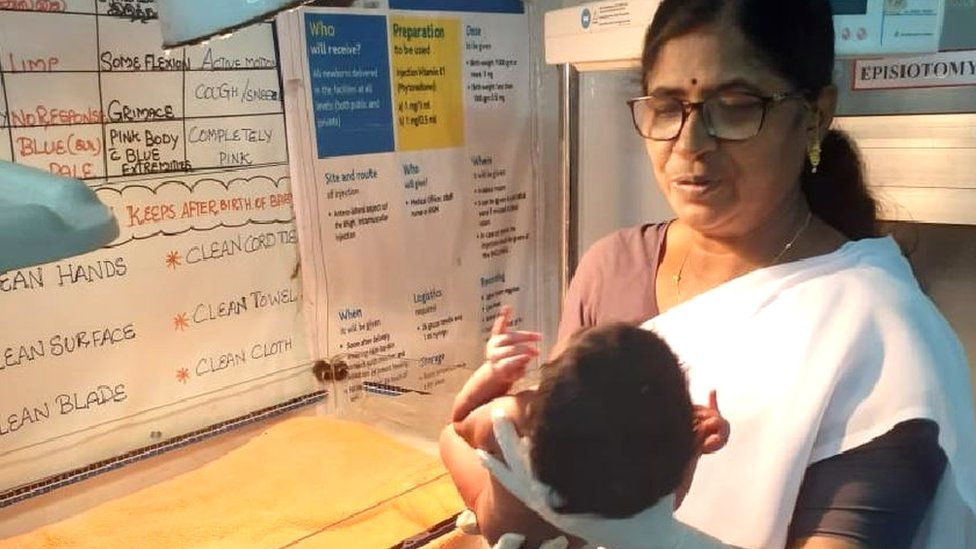

Nurses and midwives are vital for India’s healthcare system, but it faces challenges due to high demand and limited resources. Kathija Bibi, a recently retired nurse who received a government award for overseeing more than 10,000 successful deliveries, looks back on the changes she saw in attitudes towards women’s healthcare in her 33-year-long career.

“I am proud that not a single one of the 10,000 babies I delivered died on my watch,” says Kathija Bibi, 60, who counts this as the highlight of her career.

The state’s health minister, Ma. Subramanian, told the BBC that Khatija recently received a government award as no death was recorded during her years of service.

During the three decades she worked at a government health centre in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, India has transformed from a country with a high maternal mortality rate to one that is closer to the global average. She says she has also witnessed positive changes in people’s attitudes to girls being born, and towards having fewer children.

Kathija was pregnant herself when she began working in 1990.

“I was seven months pregnant… yet I was helping other women. I returned to work after a short maternity break of two months,” Kathija recalls. “I know how anxious women are when they go into labour, so making them comfortable and confident is my first priority.”

Kathija, who retired in June, radiates calm composure. Her clinic – in the predominantly rural town of Villupuram, 150km (93 miles) south of Chennai city – is not equipped to do Caesarean sections so if she detected any complications, she immediately sent pregnant women to the district hospital.

Kathija’s inspiration is her mum Zulaika, who was also a village nurse. “I used to play with syringes in my childhood. I got so used to the smell of hospital,” she recalls.

From a young age, she understood the importance of her mother’s work in providing healthcare to poor and semi-literate rural women. At that time, private hospitals were rare and women from all backgrounds relied on the state maternity home which is now called a primary health centre.

“When I started, there was one doctor, seven helpers and two other nurses,” says Kathija. “Work was very hectic in the first few years. I couldn’t look after my children. I missed family functions. But those days gave me a very valuable learning experience.”

In 1990, India’s maternal mortality rate (MMR) stood at 556 deaths per 100,000 live births. In the same year, India recorded 88 infant deaths per 1,000 live births.

The latest government figures show that MMR stands at 97 per 100,000 live births, and the infant mortality rate at 27 per 1,000 live births.

Kathija attributes this progress to government investment in rural healthcare and rising female literacy rates.

On a normal day, Kathija would handle just one or two births but she easily remembers her busiest day. “8 March 2000 was the most hectic day in my life.” It was International Women’s Day and people were greeting her as she walked into the clinic. “I saw two women in labour waiting for me. I helped them deliver their babies. Then six more women came into our clinic.”

Kathija only had one assistant to help her but the stress was soon forgotten. “When I was about to leave that day, I could hear infants crying. It was a very nice feeling.”

The nurse reckons she has helped bring into the world 50 pairs of twins and one pair of triplets.

Now, Kathija says that women from wealthy families prefer to go to private hospitals. She has also seen a surge in Caesarean sections.

“My mother saw so many deaths during childbirth. Caesareans have saved so many lives,” says Kathija. “When I started, women used to fear surgery. But now many fear natural births and are opting for surgery.”

As the income of rural households has improved in the past three decades, it has brought its own challenges. ”Gestational diabetes used to be a rare condition. But now, it’s becoming very common.”

There has been a significant societal shift as Kathija now receives a growing number of requests from husbands who eagerly want to be present during childbirth with their wives.

“I have seen bad times and good times. Some husbands would not even visit their wives if she bore a girl child. Some women would weep uncontrollably if she delivered a second or third girl.”

In the 90s, cases of sex-selective abortions and infanticide were so widely reported that the Indian government banned doctors from revealing a baby’s gender to parents. The Tamil Nadu government also launched a ‘Cradle Baby Scheme’ to take care of unwanted girls. “But now, the scenario has changed,” says Kathija. “Many couples only opt for two children, irrespective of gender.”

She has no firm plans for life after retirement, but knows what she will miss.

“I always look forward to hearing the shrill and piercing first cry of a new-born,” she says.

“You know even women who go through a painful labour, they forget everything and start smiling when they hear their babies cry. Watching that relief was such an exhilarating experience for me. It was a soulful journey for me all these years.”

Source : BBC